D. Mapping Public Health Ethics

What Can We Use to Help Us Think About Ethical Issues in Public Health?

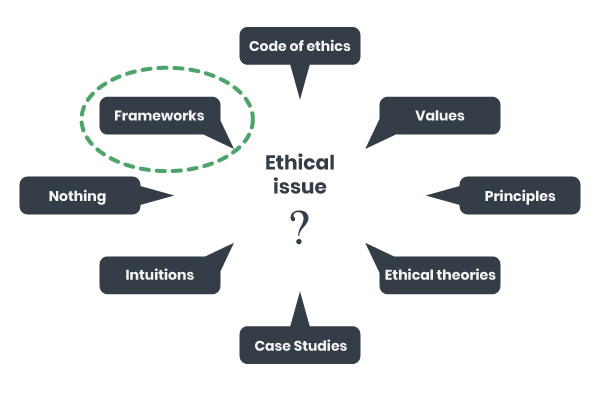

In order to identify and think about the ethical issues that arise in public health, there are a number of approaches you could take, and there are different kinds of tools available. Some of the most commonly used are codes of ethics, ethical values and principles (e.g., justice, transparency, solidarity), ethical theories like utilitarianism (based on ends, i.e., what will maximize health for the greatest number of people) or deontology (based on means, i.e., respecting persons and acting in accord with duties towards them), and using case studies to simulate real world scenarios as a way to develop skills. One might also be inclined to just use gut instinct and intuition, although this might have one relying on unstated and unconscious ethical positions, on biases, on prejudices etc. We also cannot ignore that doing nothing is another stance to doing ethics. It’s safe to say that the most common approach in public health, in the literature at least, has been in the development and use of ethics frameworks.

Approaches to Public Health Ethics

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Four Ways of Mapping Public Health Ethics

Now that we have outlined how public health ethics is situated within normative ethics and within bioethics alongside medical ethics, and having touched upon some of the various approaches to public health ethics, let’s look at what’s inside public health ethics. There are many ways of analyzing or mapping the field. We’ll look at four of them.

-

Tools or Elements Used

The first approach, based on work by Angus Dawson, involves distinguishing between the different kinds of tools or elements that are used in public health ethics. In his book chapter, Theory and Practice in Public Health Ethics (2010b), Dawson offers what he calls a “rough taxonomy” of the primary roles of theories and frameworks. According to Dawson,

- a theory is “primarily interested in the justification of action (through the suggestion of reasons why a proposed or completed action was right or wrong, or what we ought to do and why this is the case)”; and

- a framework is “primarily interested in providing some context for or assistance with deliberation about what we ought to do in a particular context” (Dawson, 2010 b, p. 193).

To these we will add codes of ethics, which are primarily concerned with professional virtues and professional character, and principles, which we will roughly define as values that are worded in a way to express that one ought to do or not do something.

First, we can consider normative ethical theories. Theories tend to involve a systematic conceptual structure that provides a moral guide for addressing any situation or specific case. Theories also focus on morally justifying decisions and actions.

Application of Normative Ethics

For example, let’s consider two such moral theories in simplified form and see how they might operate in a given situation.

In utilitarianism, the good (i.e., the ethically good) is defined as utility, which for our purposes here we can simplify to the notion of well-being. The right thing to do is to maximize well-being for the most people.

In a deontological theory, the good is related to respecting persons as ends in themselves, rather than as means to an end. The right thing to do is to act in such a way that reflects that respect for persons.

PredragImages/iStock/Getty Images

Let’s consider a fictional example: imagine a situation in which there is a critical blood shortage. Campaigns have failed and donors are not stepping up. Authorities decide to mitigate the shortage by contacting 100,000 Canadians and requiring each of them to give a unit of blood this month.

A Utilitarian Approach A Deontological Approach A utilitarian might consider whether the involuntary collection of 100,000 units of blood would produce more well-being overall than if the units were not collected in this mandatory fashion, balancing the well-being produced against the harm done to the donors, to the reduced public trust, and so on. A deontologist might start by questioning the appropriateness of requiring some people to give against their will as this action would be seen to be contrary to their agency; it would treat them as means to an end. (This is for illustrative purposes only; a real analysis would be much more nuanced.)

On the one hand, obliging blood donation produces a life-saving public good, per the utilitarian. On the other hand, it produces a cost in terms of forcing individuals to give of themselves against their will per the deontologist.

Deontological theories and utilitarianism are often placed alongside one another in situations like this one to show the fundamental ways in which they differ: utilitarianism might sometimes produce favourable outcomes but by means that we would intuitively judge unacceptable (surely there is a better way to generate donations). Deontology is seen to respect individual rights and preferences but may produce less than desirable outcomes (perhaps no one will give blood; perhaps many will die for lack of this gift). The point here is to show how two normative ethical theories account for what is good (utility or treating people as ends in themselves) and what is the right or moral thing to do (i.e., to maximize utility, or to act such that people are treated as ends, not means).

Public health ethics also uses frameworks, which are less all-inclusive than theories and one might say, more modest in their ambitions. Frameworks are intended to serve as aids to deliberation by making relevant values explicit (Dawson, 2010b, p. 196). In contrast to theories, frameworks are tools that are more intended for daily practice and which place more emphasis on deliberation. Over the past few years, since 2000 but even more so recently, many frameworks have been produced for public health ethics.

Ethics Frameworks

A framework may be as simple as a checklist of considerations, or it may be an elaborate set of guidelines with detailed procedural and methodological guidance.

For a decision-maker considering implementing an initiative such as, for example, a smoking cessation program, a typical framework will explicitly require the decision maker to consider:

- whether and how some or all people will benefit,

- whether and how some people will be harmed,

- whether the program will work,

- whether the program will increase or decrease inequalities, and so on.

Some frameworks place more emphasis on autonomy and others place more emphasis on collective goods and social justice; focusing on one or the other will tend to lead to decisions that favour one or the other.

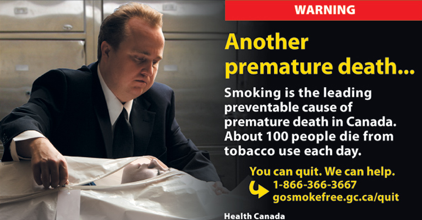

A framework that places more emphasis on autonomy might lead one to favour something like an information campaign (e.g., a health message) over a policy change that requires everyone to do or not do something (e.g., a ban on smoking).

A framework that focuses more on social justice will tend not to favour information campaigns due to their potential for increasing inequalities. Those who are better-off tend to benefit more from information campaigns, so information campaigns, in turn, tend to increase inequalities. This could exacerbate a trend that has been observed in Europe, where “smoking followed the tobacco epidemic model, according to which large inequalities appear in the latest phases of the epidemic” (Kunst, Giskes, & Mackenbach, 2004, p. 6) due to lower rates of smoking cessation among those in certain occupational groups, with less formal education, and low income groups.

In public health ethics, principles play a key role and are often appealed to. Principles refer to values, and are worded in a way to express that one ought to do or not do something. Principles are often found in frameworks.

Application of Ethical Principles

In pandemic preparedness plans, we often see references to the principle of reciprocity. Reciprocity is suitable for an ethics framework focusing on pandemics because in times of pandemic, professionals and citizens are called upon to make sacrifices for the common good: workers are expected to put themselves at risk by continuing to show up to do their duty; citizens are called upon to stay home from work if they become ill.

U.S. Air Force photo/ Airman 1st Class Anthony Jennings. Retrieved from https://www.eglin.af.mil/News/Photos/igphoto/2000369037

Reciprocity reflects the importance of recognizing these sacrifices and supporting both workers and citizens to enable them to do their part for the common good, or to compensate them for harms they suffer as a result. That might mean recognition, compensation, insurance, etc. The principle of reciprocity, among others, has a role to play in ethics frameworks because it is brought forward to remind us that there are important values and issues that have to be considered when pandemic responses are planned and executed. Different situations in public health will bring different values and principles to the fore.

Finally, public health ethics also includes codes of ethics. Codes often take the form of a series of general guidelines about what to do or not do as a public health professional. These guidelines can often be seen as being about professional virtues or character.

Codes of Ethics

The Canadian Nurses Association (2017) Code of Ethics for Registered Nurses provides a good example of a professional code of ethics in Canada. In the section entitled Purpose of the Code, the authors provide an outline of what a code of ethics can set out to do: its functions include

- setting out values;

- describing the kinds of responsibilities and actions that should issue from those values;

- providing a regulatory framework setting out the boundaries of acceptable practice; and

- providing guidance for ethical relationships, behaviours and decision making (Canadian Nurses Association, 2017, p.2)

Canadian Nurses Association

[CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], from Wikimedia CommonsAs codes of ethics go, this one has much in common with ethics frameworks in that it provides not just aspirational elements like declarations of professional values but also guidance for ethical practice in specific situations.

We will return to say a bit more about values, principles and frameworks in a later section of this module.

-

Four Distinct Ethical Perspectives

Another way of mapping the field of public health ethics, proposed by Lawrence Gostin, was to think about it in terms of ethics of public health, ethics in public health, and ethics for public health. To these three Callahan and Jennings added a fourth type of public health ethics, critical public health ethics.

Ethics of Public Health:

- Professional ethics

- codes of ethics

Ethics in Public Health:

- Applied ethics

Ethics for Public Health:

- Advocacy ethics

- for the value of healthy communities

Critical Public Health ethics

- Questions the givens

- How it is framed

- Underlying power relations

-

Professionalism and Codes of Ethics

Ethics of public health is the part that is concerned with professionalism and codes of ethics.

Professionalism and Codes of Ethics

As we saw with the Canadian Nurses Association Code of Ethics, some codes do provide guidance for specific situations. Another example of a code of ethics that is conceived of and used like an ethics framework (in that it helps to raise issues and guide practice) is the US Public Health Leadership Society’s (PHLS) Principles of the Ethical Practice of Public Health. Its guidelines are high-level but also specific to practice.

For example, two such guidelines are:

Public health institutions should provide communities with the information they have that is needed for decisions on policies or programs and should obtain the community’s consent for their implementation.

...

Public health institutions should ensure the professional competence of their employees.

Other codes of ethics are more clearly focused on professionalism and the character of the practitioner than about what to do in a given situation. While these codes do provide some guidance about how to do the job, it will in general be more about how to be a professional than about what to do.

For example, in the Canadian Institute of Public Health Inspectors (CIPHI) Code of Ethics, the obligations of environmental public health professionals that issue from the various principles include:

Ensure that personal issues do not compromise professional performance

Always strive to behave in an honourable fashion

There is nothing wrong with this; it is quite simply different, in general, from what the majority of public health ethics frameworks set out to do. It is more about being the kind of person who will do the right thing than it is about deliberating to determine the right thing to do in a specific situation when there is not a clear course of action.

(It must also be noted that some requirements in this code of ethics are more of a kind with ethics frameworks, including for example, requirements to avoid conflicts of interest and to protect confidentiality, just to name two. These examples simply indicate that the conceptual boundaries between codes of ethics and frameworks and not cut and dried – they are fluid; but we can observe tendencies nonetheless.)

-

Applied Ethics

Ethics in public health relates to applied ethics, that is, guidance for practitioners in specific situations when general rules or codes of ethics do not provide sufficient clarity or orientation.

Applied Ethics

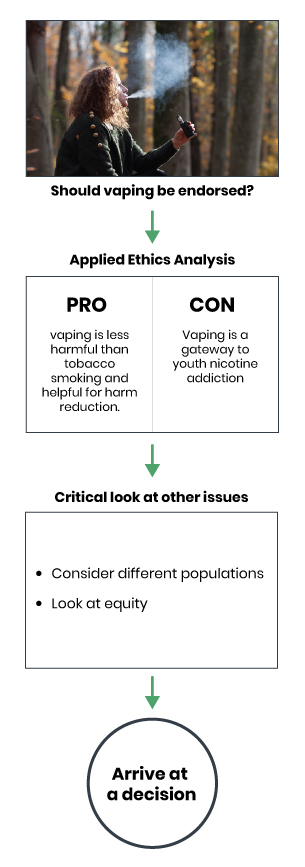

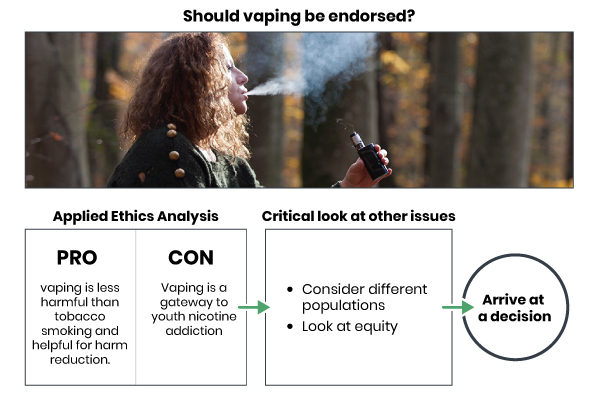

Applied ethics is largely our focus in later parts of this module. It is about making a decision about what to do in a particular situation. When a practitioner or decision maker is confronted with questions about whether a program, policy or intervention is the best course of action, their choice can be informed by ethical analysis. We will encounter several case studies later on that will give you the opportunity to practise ethical deliberation on concrete examples. For a preview of the sort of problem that may be the subject of applied ethics in public health, questions surrounding a public health approach to e-cigarettes and vaping are interesting. For example, some argue that vaping is much less harmful than tobacco smoking and therefore should be encouraged from a harm reduction perspective. Others will point out that vaping can be seen as cool among young people and can therefore act as a gateway to nicotine addiction among those who may not otherwise have been tempted. An applied ethics analysis will set out to consider the various pros and cons relating to a proposal, the various benefits and harms that will be faced by different population groups, in an effort to arrive at a decision as to whether to proceed with an initiative, to amend it to produce more benefits and less harms, to proceed with an alternative, or to not proceed. Applied ethics will also focus on equity issues by taking a critical look at which groups are at greater risk for ill health and why.

bulentumut/E+/Getty Images

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo -

Advocacy Ethics

Ethics for public health has been described as advocacy ethics, because it is about the importance of the values that underlie public health and which the field seeks to promote, like improving the health of the population and reducing health inequities.

Public Health Advocacy

One example of public health advocacy is the initiative by Toronto Public Health to ensure that the health impacts of gambling were part of the discussion about whether to open a new casino.

Reading

You can read more about this example of public health advocacy here: The Health Impacts of Gambling Expansion in Toronto – Technical Report. Toronto Public Health. (2012)

.

.

Hispanolistic/E+/Getty Images

Public health engaging in such public discussions is sometimes considered problematic because a public authority may be seen to be going against the expressed interests of the government that funds it; it may be seen as acting outside of its mandate when touching upon subjects as diverse as gambling, transportation, education, etc. In addition, practitioners and institutions put themselves at risk when they enter into advocacy roles against some corporate interests, through the potential for lawsuits and other tactics. However, public health has a mandate to improve health and reduce inequalities, and is empowered to act by public health legislation. As such, we might say that public health is obliged to get into the mix.

Advocacy ethics will consider the issues relating to acting or not acting to advance health within the charged political terrain of a casino development process, for example.

Advocacy in Public Health

Approaches to Public Health Advocacy

(PPT).

(PPT).

Brooks, E. (2017).Public Health Advocacy

.

.

Alberta Health Services. (2009).Health promotion, advocacy and health inequalities: A conceptual framework

.

.

Carlisle, S. (200). Health Promotion International, 15(4), 369-376.Advocacy for Public Health: A Primer

.

.

Chapman, S. (2004). Journal of Epidemiology and Public Health, 58, 361-365.Advocacy: It’s Not a Dirty Word, It’s a Duty

.

.

Hancock, T. (2015). Canadian Journal of Public Health, 106(3), e86-e88.Healthy Public Policy Toolkit: Advocacy

.

.

Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. (2017). -

Critical Public Health Ethics

To these three, Callahan and Jennings suggested adding a fourth type of public health ethics: critical public health ethics. This calls upon public health practitioners to step back in order to take a critical posture when considering situations, by questioning the things that are taken for granted, how problems are framed, and the power relations that underlie them.

Two Approaches to Mapping Public Health Ethics in Practice

Before we continue with the mapping, just in order to better clarify the difference between ethics in public health/applied ethics and critical public health ethics, let’s look at our Ebola ethical dilemma again.

Ethical Dilemma: Ebola

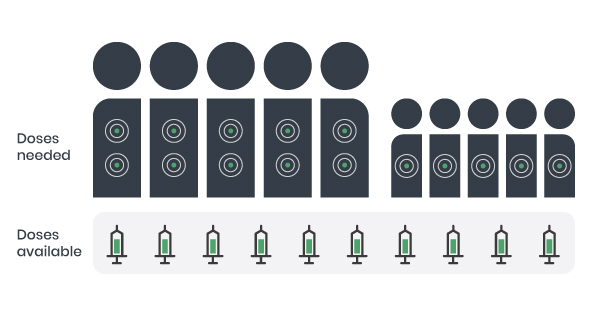

Imagine that you work in a clinic and 10 patients that are infected with Ebola are all admitted at once. There are five adults and five children. Among the adults are 2 volunteer care workers. You have only 10 doses of an antiviral medication, but the treatment requires 2 doses for adults and 1 dose for children to be effective. Because you do not have enough doses to treat everyone, you must decide how to distribute them.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Ethics in PH

Make a Decision: What should you do?

- give one dose to everyone

- give one dose to each child and 2 doses to 2 adults

- organize a lottery (random assignment to individuals)

- give the doses to the most disadvantaged first?

- treat the care workers first?

Critical PH ethics

Question the situation itself

- Why do I have only 10 doses of an experimental antiviral after 42 years of Ebola?

- What social structures produced this situation?

- Would this situation be treated differently if it were in North America?

Ethics in public health has us trying to make a decision about what we ought to do in a given situation, in this case allocating scarce resources for responding to ten people who need them. That was how we set up the initial exercise – it was essentially a question for applied ethics. The critical perspective goes further by questioning the situation itself and the options that are presented as being the possibilities, given the situation. A critical public health ethics perspective could lead us to ask questions like: Why do we have only 10 experimental doses after 42 years of Ebola? What social structures produced this situation? Would this situation be treated differently if Ebola was endemic to North America?

A critical perspective is essential for doing ethics in public health. We say this because without a critical perspective to complement it, applied ethics and the decisions that result might be unnecessarily or inappropriately limited by the range of possibilities that are defined by and presented as the givens.

Finally, it is also useful to note that all of these four perspectives (ethics of, in and for public health, and critical public health ethics) complement one another and may be in operation simultaneously in practice. That they represent different ways of thinking or looking at issues does not mean they are exclusive. Indeed, they are all important to bring into play as lenses to help inform ethical practice.

-

Research and Practice

A third way of representing the field of public health ethics is to separate research ethics from practice. This includes any activity that involves data collection, storage, and the presentation of findings. It may involve ethics review boards or research ethics committees.

Research ethics emerged in response to a host of shocking abuses of research subjects by researchers who used their subjects without attempting to help them, and often actively harmed them. Well-documented examples include Nazi doctors during WWII and the infamous Tuskegee Syphilis Study (see Brandt, 1978), among others. Research activities involving human subjects are now subject to ethics review and the area of research ethics is oriented around protecting those who are the sources of data to ensure that their rights are protected, that they provide informed consent to their participation, etc.

Research Involving Humans

TCPS2. Tri-Council Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans

.

.

Interagency Advisory Panel on Research Ethics. Government of Canada. (2014).This document, known as the TCPS2 or the Tri-Council Policy Statement, is Canada’s reference document on research ethics. It provides guidelines and principles for the conduct of ethical research and includes a chapter on considerations for interpreting the ethics framework for applying in the context of research involving First Nations, Métis and Inuit peoples of Canada.

In addition to this research-practice distinction, we note the discussions that have been emerging over recent years about the ethics of quality improvement initiatives, evaluation, surveillance and the like, and the development of ethical standards related to these activities in distinction from research ethics. These public health activities also generate evidence but are generally not subject to ethics review as research activities are.

Beyond the Research-Practice Distinction

Surveillance

Surveillance is a key activity in public health, and involves the “[s]ystematic ongoing collection, collation and analysis of data for public health purposes and the timely dissemination of public health information for assessment and public health response as necessary” IHR – International Health Regulations (2005) in (WHO, 2016, p. 10). Surveillance has much in common with research, but is generally not treated in the same manner (i.e., it is not usually subject to ethics review by institutional ethics boards). The two documents below provide a helpful overview of the sorts of ethical issues that arise in surveillance.

Surveillance

Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance A Systematic Qualitative Review

.

.

Klingler, C., Silva, D. S., Schuermann, C., Reis, A. A., Saxena, A., & Strech, D. (2017). BMC Public Health, 17:295.WHO Guidelines on Ethical Issues in Public Health Surveillance

.

.

World Health Organization. (2017). Geneva: World Health Organization.Quality improvement, program evaluation, needs assessments, etc.

Many public health activities generate evidence and do not fall into the category of research. In efforts to provide ethical oversight of all activities, without creating inappropriate hurdles to such initiatives, new tools have been developed for assessing the sort of project that is being proposed, and therefore finding appropriate degrees of ethical oversight necessary.

Assessment Tools

Arecci Ethics Guideline and Screening Tools

.

.

Alberta Innovates. (2017).Risk Screening Tool

.

.

Public Health Ontario. (2017).A Framework for the Ethical Conduct of Public Health Initiatives

.

.

Public Health Ontario. (2012). -

Core Public Health Activities

A fourth way of looking at public health ethics is to turn to public health practice itself. If we start out by looking at the main categories of public health activity, like health surveillance, health protection, disease and injury prevention, emergency preparedness and response, health promotion and population health assessment we could find that different sorts of ethical issues will tend to come to the foreground according to the aims and actions within these different sorts of work. In surveillance, we might find issues of privacy, confidentiality, consent and stigmatization come to the fore. In health promotion we might consider issues of advocacy and political activism and the boundaries that practitioners face, or individualistic approaches to lifestyle and choice versus structural approaches.

© Course Author(s) and University of Waterloo

Core public health functions of public health in Canada are health surveillance, health protection, disease and injury prevention, emergency preparedness and response, health promotion, and population health assessment (Chief Public Health Officer, 2008, pp. 8-9). Let’s reframe them as core public health activity areas, and add three more activity areas that arguably deserve a place among them. For the sake of argument, let’s add in global health, ecological health, and reconciliation. Reconciliation would include implementing the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action (2015). Each of these represents a facet of public health in 2019, and we propose that these nine could all be focal points for the study of public health ethics in Canada.

Mapping Public Health Ethics

In the section above, we presented four ways of mapping public health ethics, according to:

- the tools or elements used

- the ethics of, in, for public health and critical public health ethics

- the distinction between research and practice

- core public health activities.

If someone were to present your group with an ethics framework, which way of mapping or looking at public health ethics would be applicable to interpreting and using that ethics framework?.